The Satyajit Ray Centenary Show (Volume I)

A centenary show is a testament to the pertinence of an artist even after 100 years. The relevance of works of a giant like Satyajit Ray has only evolved with time. The splendour of his genius remains untarnished. KCC presented The Satyajit Ray Centenary Show (Volume I) in collaboration with Gallery Rasa in January as a tribute to the Master. The exhibition proudly showcased lesser-known aspects of Ray’s work like his lobby cards, pressbooks, posters, costumes and props used in the films and book covers –– divulging the creative process behind his meticulous designing –– along with rare photographs of the master at work by Nemai Ghosh. One can say that we tried to bring forth the ‘Other Ray’. When some of these were shown in an exhibition organised at The Village Gallery by Mrs. Dolly Narang in 1990, Satyajit Ray him- self wrote a note that sheds light on his thought process and his opinion about his other works.

2022-01-29 12:41:07.jpg)

A centenary show is a testament to the pertinence of an artist even after 100 years. The relevance of works of a giant like Satyajit Ray has only evolved with time. The splendor of his genius remains untarnished. We are glad to present The Satyajit Ray Centenary Show (Volume I), in collaboration with Gallery Rasa. The exhibition proudly showcases lesser-known aspects of Ray’s work like his lobby cards, press books, posters, costumes, and props used in the films and book covers— divulging the creative process behind his meticulous designing—along with rare photographs of the master at work by Nemai Ghosh. One can say that we have tried to bring forth the ‘Other Ray’. When some of these were shown in an exhibition organized at The Village Gallery by Mrs. Dolly Narang in 1990, Satyajit Ray himself wrote a note that sheds light on his thought process and his opinion about his other works:

My grandfather was, among other things, a self-taught painter and illustrator of considerable skill and repute, and my father—also never trained as an artist— illustrated his inimitable nonsense rhymes in a way which can only be called inspired. It is, therefore, not surprising that I acquired the knack to draw at an early age.

Although I trained for three years as a student of Kalabhavan in Santiniketan under Nandalal Bose, I never became a painter. Instead, I decided to become a commercial artist and joined an advertising agency in 1943, the year of the great Bengal famine. Not content with only one pursuit, I also became involved in book designing and typography for an enterprising new publishing house.

In time I realised that since an advertising agency was subservient to the demands of its clients, an advertising artist seldom enjoyed complete freedom.

This led me to the profession of filmmaking where, in the 35 years that I've been practising it, I have given expression to my ideas in a completely untrammelled fashion.

As is my habit, along with filmmaking, I have indulged in other pursuits which afford me the freedom I hold so dear. Thus, I have been editing a children's magazine for thirty years, writing stories for it and illustrating them, as well as illustrating stories by other writers. While preparing a film, I've given vent to my graphic propensities by doing sketches for my shooting scripts, designing sets and costumes, and even designing posters for my own films.

Since I consider myself primarily to be a filmmaker and, secondarily, to be a writer of stories for young people, I have never taken my graphic work seriously, and I certainly never considered it worthy of being exposed to the public…I must insist that I do not make any large claims for them.

Although Ray insisted on not making “large claims”, his ‘other’ works are all a testament to his genius. Every work makes the viewer engage in deep contemplation. We hope that the viewers get to experience the artistic genius of Ray as they stand before his mammoth body of work. The artistic flair and flourish are palpable in the designs. Nemai Ghosh’s photographs further enhance the experience where Ray’s intense gaze and innocent laughter resonate through the exhibition space. The original costumes and props exhibited here also add an air of authenticity. Every element present in this space throbs with memories, adding to the ever-growing fabric of memories of the viewers.

Lobby cards:

Lobby cards occupy a position between movie posters and the still photographs taken during the shooting of the movie. They came into existence when larger theatres with lobby space for advertisement began to be built. They gave a foretaste of the movie to the viewers before they entered the hall and simulated their imagination, just as the trailers, which came later, do today. Lobby cards became commonplace in America during the 1930s and came to India a little later. But when they arrived, they became a popular way of introducing the actors and key moments of the film to a potential audience. So, in addition to the beautiful, colourful lithographic movie posters, photographic images in the form of lobby cards emerged as an effective way of publicising the movie.

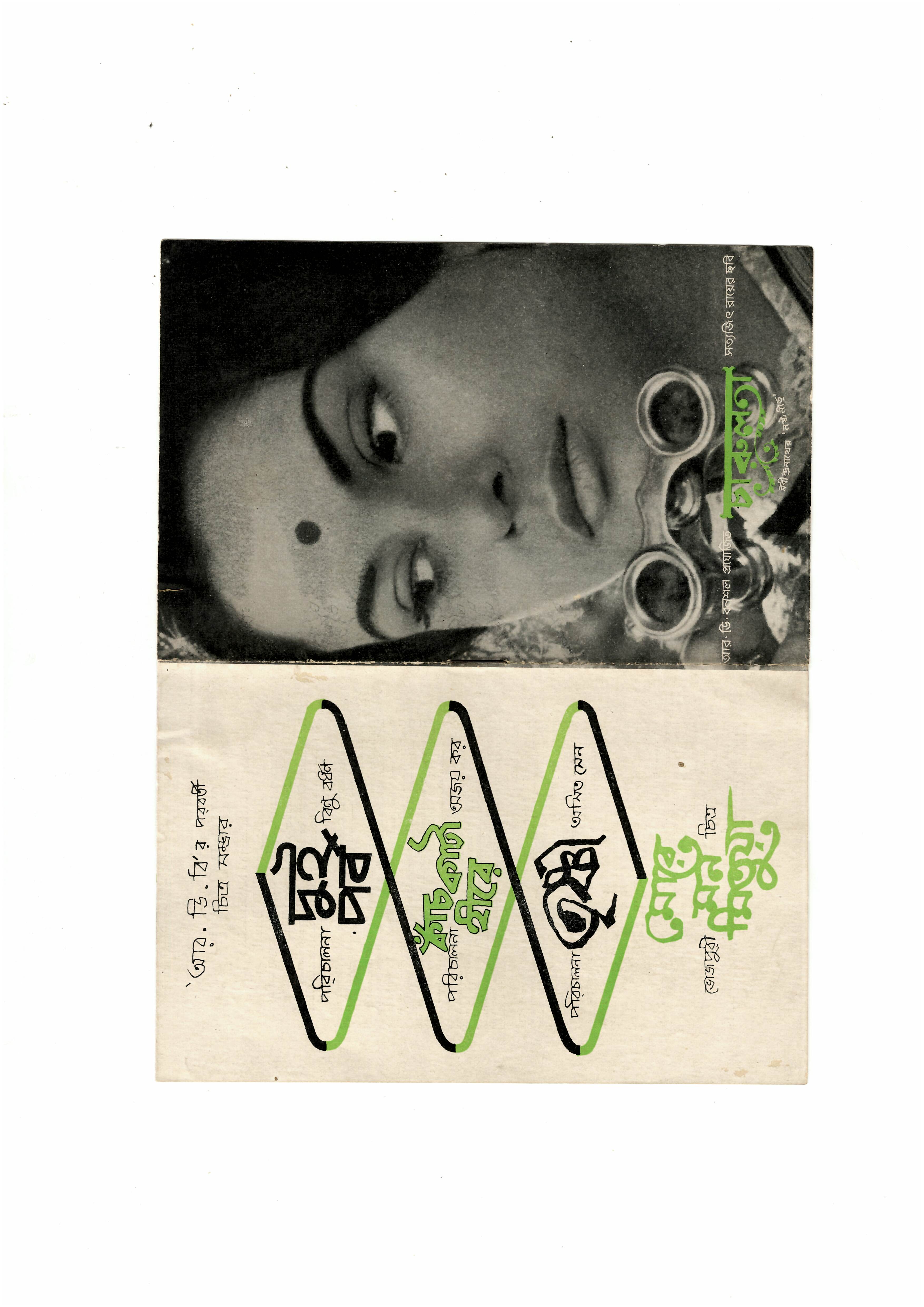

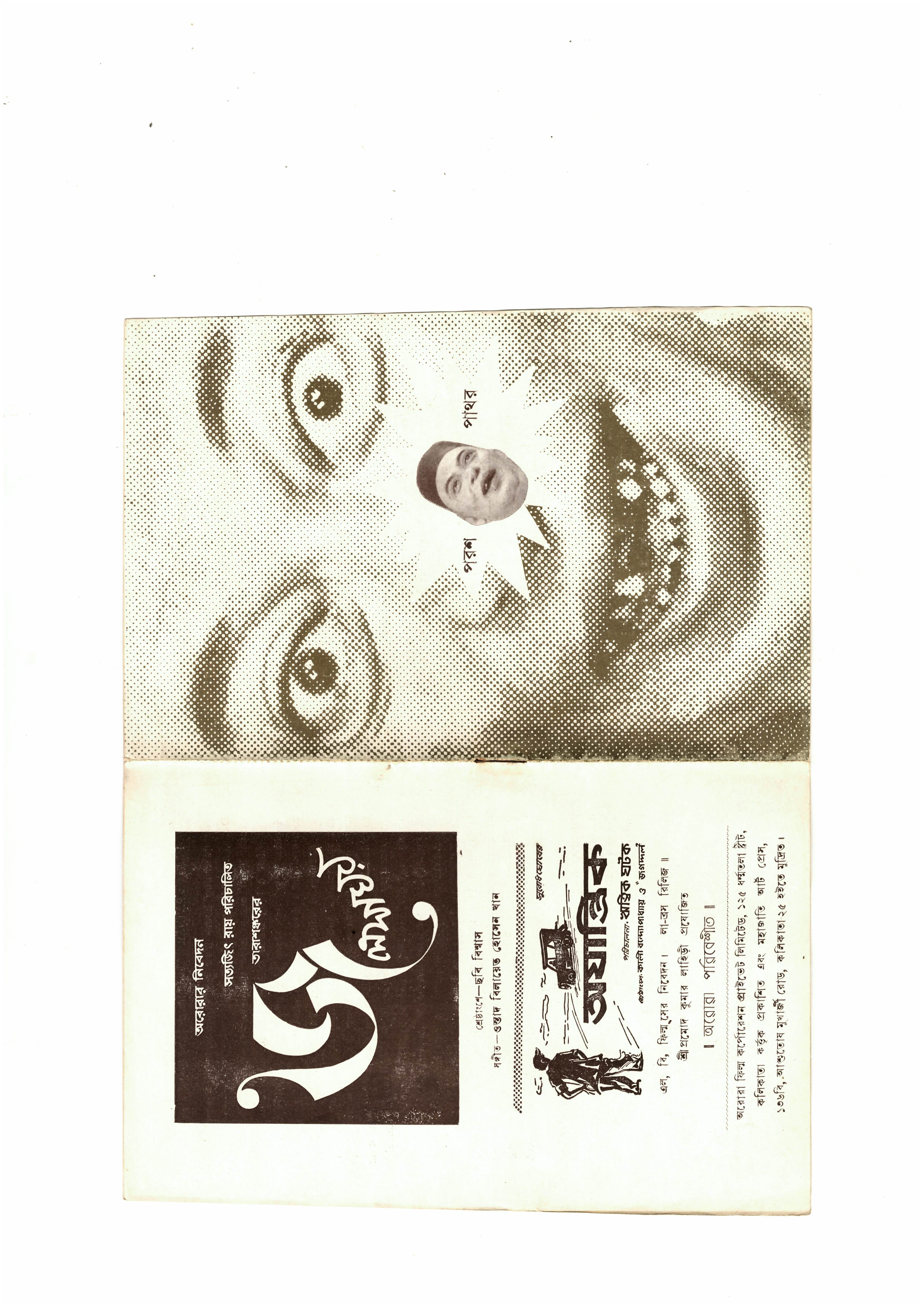

Pressbooks:

A pressbook could be viewed as a flyer or brochure that revealed information about the plot, characters and actors in the films and also included the song lyrics. The purpose behind a pressbook was to generate awareness among the people and to give them an idea of what to look forward to. It was a promotional material made by the production houses and the distributors and used to be a part of the film's campaign kit. If one may be so bold, one can even think of them as precursors to the present-day teaser trailers.

Ray’s pressbooks, as can be observed here, were minimalistic in approach, incorporating motif(s) and character(s) from the films. They were often designed using different layouts and were available in both English and Bengali. It is interesting to note that the pressbooks were at times also used as promotional materials for other films by the same production house. For instance, at the back of the pressbook for Parash Pathar, one can spot a cartoonish advertisement for Ritwik Ghatak’s Ajantrik, also released by Aurora Film Corporation. Although some design elements remain the same, it is not difficult to understand where Ray's design ends. In the case of Charulata, there is also an advertisement for a Bhojpuri film produced by R.D. Bansal where the green and black colour scheme used by Ray remains intact. Ray's meticulous designing can be observed in pressbooks like that of Ghare Bhaire. It is worth noting that when it came to films like Agantuk, there were no advertisements for other films as they were produced by the National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC) or other bodies under the Government."

Ray’s pressbooks, as can be observed here, were minimalistic in approach, incorporating motif(s) and character(s) from the films. They were often designed using different layouts and were available in both English and Bengali. It is interesting to note that the pressbooks were at times also used as promotional materials for other films by the same production house. For instance, at the back of the pressbook for Parash Pathar, one can spot a cartoonish advertisement for Ritwik Ghatak’s Ajantrik, also released by Aurora Film Corporation. Although some design elements remain the same, it is not difficult to understand where Ray's design ends. In the case of Charulata, there is also an advertisement for a Bhojpuri film produced by R.D. Bansal where the green and black colour scheme used by Ray remains intact. Ray's meticulous designing can be observed in pressbooks like that of Ghare Bhaire. It is worth noting that when it came to films like Agantuk, there were no advertisements for other films as they were produced by the National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC) or other bodies under the Government."Posters:

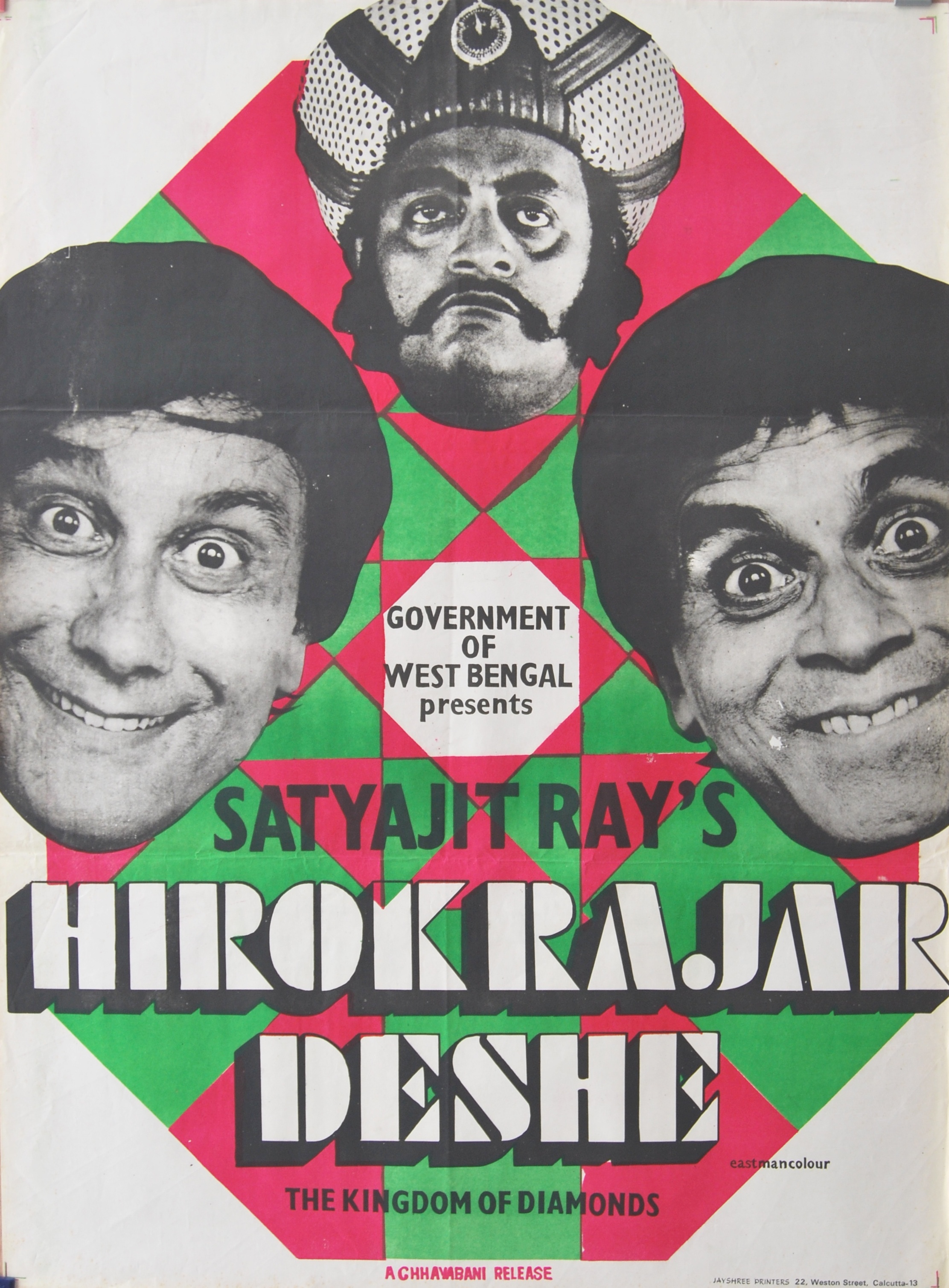

It is no wonder that Ray’s exceptional skills and aesthetic sense, coupled with his training in Calligraphy, led to his designing many posters for his own films. A designer par excellence, Satyajit Ray also made and experimented with English and Bangla typefaces, the use of which can be viewed in his posters.

.JPG)

Ray’s posters weren’t gaudy, attention-grabbing advertisements. Since a good wine needs no bush, the posters were more than mere advertisements for Ray’s films. Even in this digital age, Ray’s lithographic posters have stood the test of time, having transcended their utilitarian values to evolve into works of Art in their own right. The blending of Pop elements and traditional Indian art forms with an undercurrent of Bauhaus influence lent his posters a strikingly unique quality - achieving a balance between functionality and aesthetics.

Ray’s posters weren’t gaudy, attention-grabbing advertisements. Since a good wine needs no bush, the posters were more than mere advertisements for Ray’s films. Even in this digital age, Ray’s lithographic posters have stood the test of time, having transcended their utilitarian values to evolve into works of Art in their own right. The blending of Pop elements and traditional Indian art forms with an undercurrent of Bauhaus influence lent his posters a strikingly unique quality - achieving a balance between functionality and aesthetics.

Costumes:

Costumes are an integral part of characterisation. Ray, being the meticulous director and designer that he was, paid critical attention to the costumes of his characters. He designed the costumes himself and even insisted on the correct fabric for each garment. His costumes are true to the character, to the time period being depicted.

For instance, in the film Parash Pathar (1958), Paresh Dutt played by Tulsi Chakraborty, is a middle-class bank clerk who wears a white dhoti and shirt throughout the film except in the cocktail party scene where he is seen wearing black woollen trousers with a white coat to denote his newly acquired wealth and social status.

In Jalsaghar (1958), the landlord Biswambhar Roy, played by Chhabi Biswas, was clad in dhoti and panjabi paired with nagra — lending an authentic touch to his character of a zamindar. In the film, Kanchenjungha (1962), the character of Anima, played by Anubha Gupta, wore a saree with a black coat that shows the fusion of Indian and Western elements, just like the character herself.

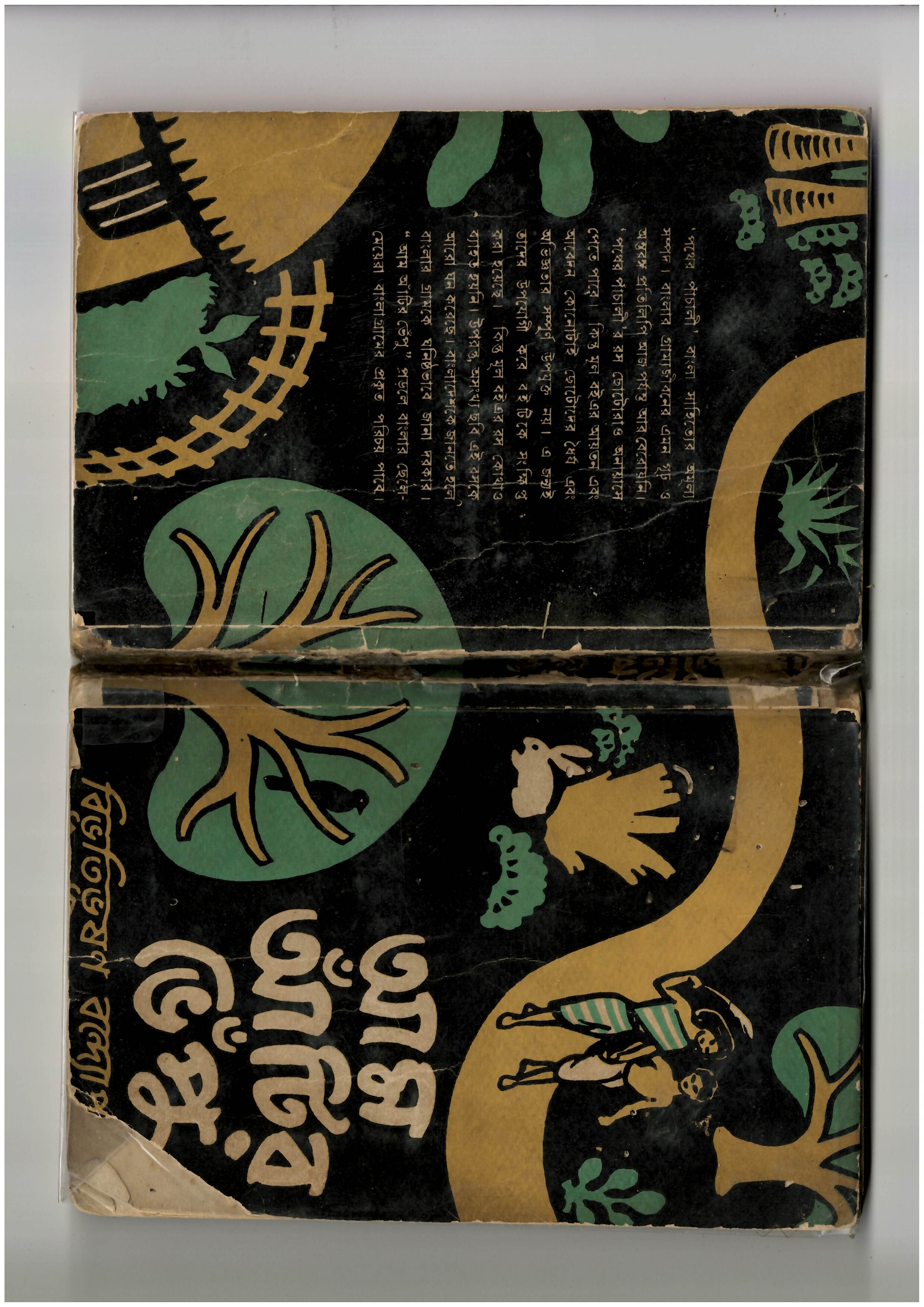

Designing Book-Covers:

Although the filmmaker has reigned supreme, it is a shame that Ray the illustrator remains so underrated. Growing up in a creative milieu, Satyajit Ray had an early exposure to Visual Arts, which was further honed through his formal training in Santiniketan. Ray joined Kala Bhavana in 1940 to learn drawing, painting, and calligraphy, along with Indian Art in all its forms which informed his creative output, including his illustrations, later on.

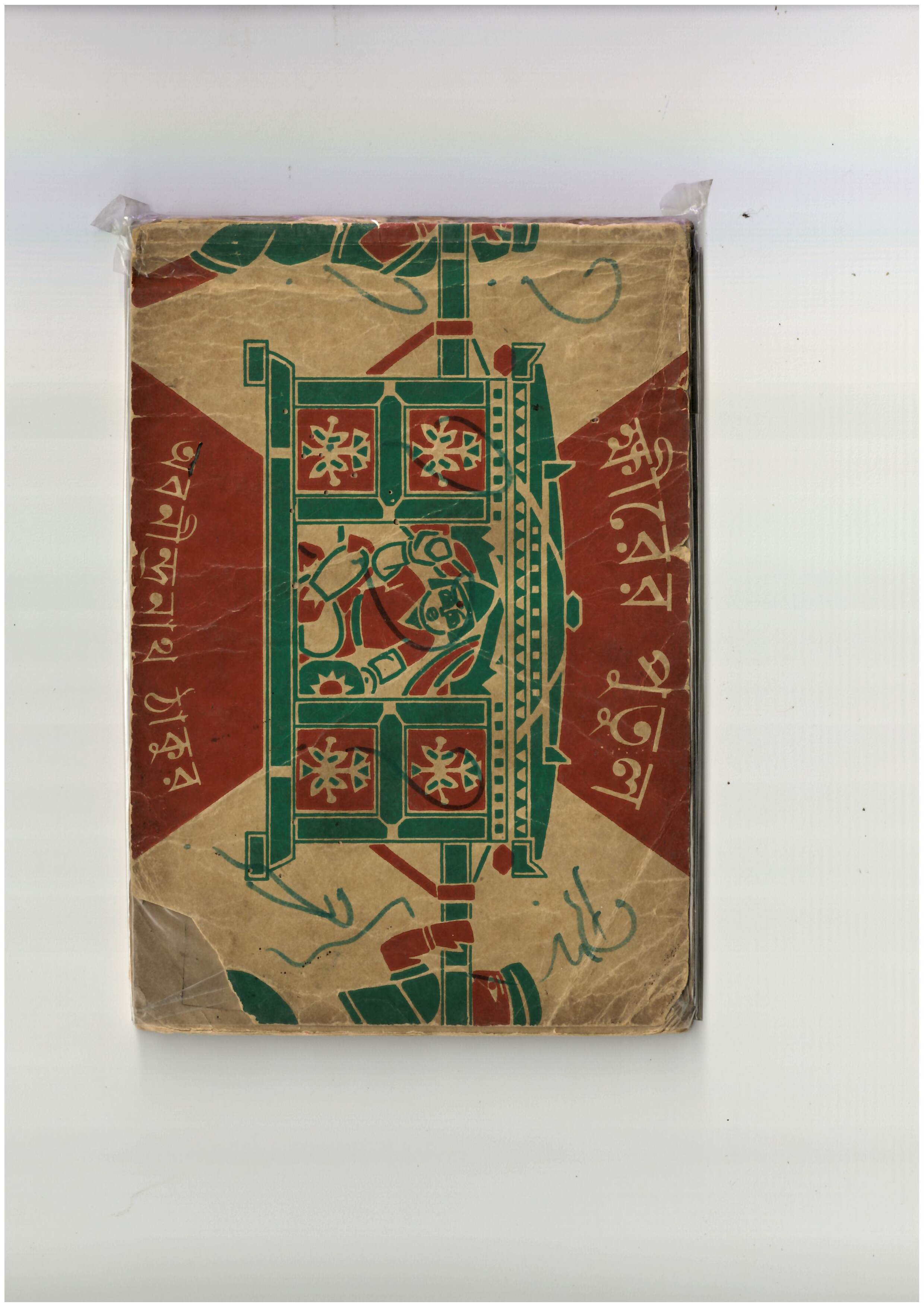

His association with the publication house ‘Signet Press’, founded in 1944, turned out to be a boon for the illustrator in Ray, and he steadily rose to prominence. He has illustrated and designed the covers for some of the finest works in Bengali literature, including Abanindranath Tagore’s ‘Khirer Putul’ and Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s ‘Aam Antir Bhepu’. While he took inspiration from and adapted folk motifs from Bengal for ‘Khirer Putul’, Ray took inspiration from one of his mentors Nandalal Bose and integrated the linocut effect in his illustrations for ‘Aam Antir Bhepu’. The latter spurred him to make his first film, ‘Pather Panchali’, in 1955. He drew inspiration from varied sources – from the Bauhaus to miniature Rajput paintings. It is awe-inspiring, to say the least, how far his creative genius expanded.

His association with the publication house ‘Signet Press’, founded in 1944, turned out to be a boon for the illustrator in Ray, and he steadily rose to prominence. He has illustrated and designed the covers for some of the finest works in Bengali literature, including Abanindranath Tagore’s ‘Khirer Putul’ and Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s ‘Aam Antir Bhepu’. While he took inspiration from and adapted folk motifs from Bengal for ‘Khirer Putul’, Ray took inspiration from one of his mentors Nandalal Bose and integrated the linocut effect in his illustrations for ‘Aam Antir Bhepu’. The latter spurred him to make his first film, ‘Pather Panchali’, in 1955. He drew inspiration from varied sources – from the Bauhaus to miniature Rajput paintings. It is awe-inspiring, to say the least, how far his creative genius expanded.Paritosh Sen on Ray:

Satyajit was … under the very able guidance of Benode Behari Mukherjee, a great artist and an equally great teacher. Besides, Ray had also the unique opportunity of coming in close contact with Nandalal Bose, the guru of both Benode Behari and Ram Kinkar, undoubtedly the foremost sculptor of contemporary India.

Earlier he had also received the blessings and affection of Rabindranath Tagore. Although he did not complete the art course in Santiniketan, the experience of being surrounded by these great artists and the unique rural setting of the Santhal Parganas, as portrayed by these artists and the poet, enabled Ray to appreciate nature in all its diverse and glorious manifestations and opened his eyes to the mysteries of creation. This single unprecedented and cherished experience helped him to formulate his ideas about the visual world and to unlock doors of visual perceptions. Added to this was his study and understanding of the classical and folk art, dance and music of our country. The magnificent collection of books in the Santiniketan library of world art and literature also helped him to widen his horizon. It was here that he read whatever books were available on the art of cinema. The seeds of a future design artist and a filmmaker were simultaneously sown here.

Paritosh Sen

The Other Ray

Nemai Ghosh on Photographing Ray:

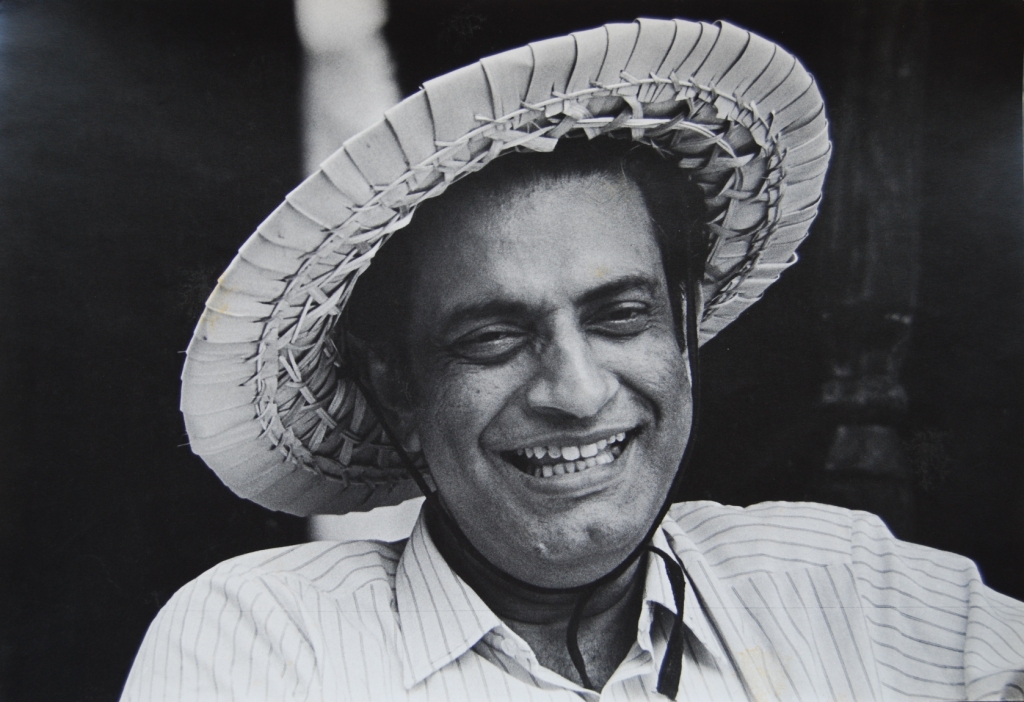

The year was 1968, and Robi was acting in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha). I went along with some friends to watch him in a remote village in West Bengal. Someone happened to lend me a camera and I took a few pictures. I had no plan, but somehow, ever since then, I have been following Manikda like a shadow, though I admit I cannot always cope with his amazing pace.

He never asks me questions when I photograph him. He gets on with his work. I take my pictures. Often he is so absorbed that I am hesitant to request permission. But the light and the composition are so perfect that I am desperate to shoot. Why suffer? I begin, and soon 36 shots have been taken. Manikda does not even notice. Afterwards, seeing the pictures, he frequently asks me, 'When did you take it?"

Whatever he is doing - whether he is writing, designing, acting, directing, editing, composing or simply pondering - Manikda is preoccupied by the work. When I look into his eyes, I feel I can see the whole film visualised there. I try to catch that impression in my pictures.

But he can also smile like an innocent child.

And that too I try to capture, sometimes at work, often during gaps in the work. For me Manikda is like oxygen: any time I feel low, I only need to go and have a look at his inspiring personality and I am refreshed.

Nemai Ghosh

Satyajit Ray at 70

*This note has been reprinted here courtesy of Shri Satyaki Ghosh, S/O Shri Nemai Ghosh

.jpg)

2022-01-29 12:41:45.jpg)