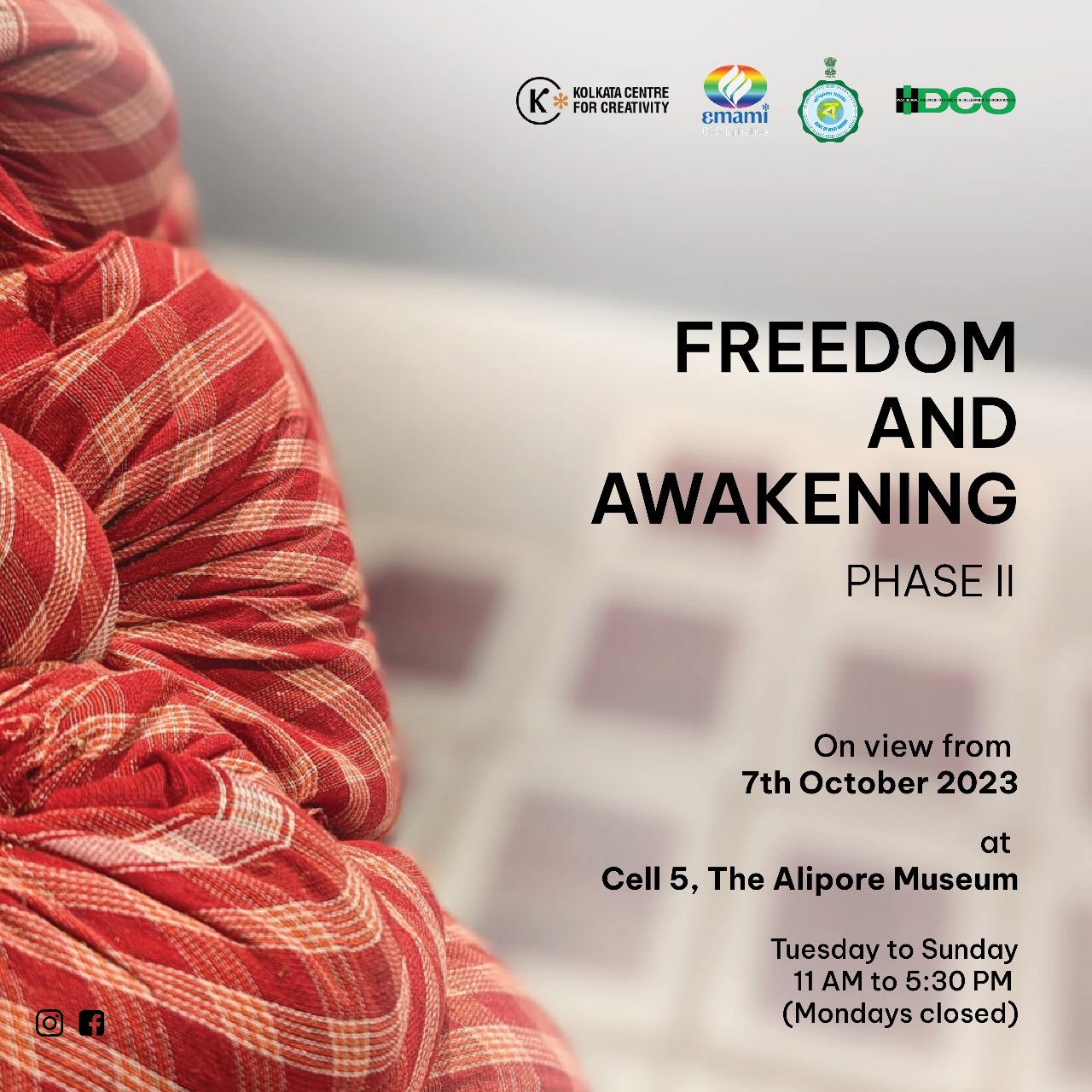

Freedom and Awakening Phase II at Alipore Jail Museum

FREEDOM AND AWAKENING: PHASE 2

To celebrate the opening of the Alipore Museum, Kolkata Centre for Creativity (KCC) in collaboration with the Government of West Bengal curated an exhibition titled ‘Freedom and Awakening’. This exhibition, which is being displayed in multiple phases, brings together prominent and promising artists from all over India to explore the ideas of freedom on the road to awakening. The foundational ideals that birthed India are intellectually probed and presented artistically.

After a year-long successful run of the first phase of the exhibition, the second phase is now ready for viewing through artworks by contemporary Bengali artists namely Chhatrapati Dutta, Mithu Sen, Debasish Mukherjee, Smarak Roy, Chandra Bhattacharjee, Suman Dey, Arunima Choudhury and Debanjan Roy.

Curatorial Note

75 years ago, at the stroke of midnight, India became free from the clutches of coloniality. Years of freedom struggle, uncountable martyrdoms and a deep gash of Partition later, India finally became independent on 15th August 1947.

The struggle for freedom was not only a matter of Independence from the British, but it also implied an awakening. As the ending of Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘Where the Mind is Without Fear’ suggests, it was an expression of our collective aspiration to awaken into a heaven of freedom. The political journey to attain this freedom brought with it a cultural awakening.

Abanindranath Tagore is widely recognised as the visionary behind a new Indian art that embraced nationalist ideals. His emblematic representation of Bharat Mata, infused with political significance, symbolised Indian nationalism. Rabindranath Tagore’s influence ushered in a holistic resurgence, challenging the prevailing Western modernism and revivalist nationalism in the realm of arts and aesthetics. Artists like Nandalal Bose and Ramkinkar Baij carried forward this vision, fusing modernism with cultural roots and cross-cultural encounters. Nandalal, for instance, intertwined art with politics through creations like the iconic portrayal of Gandhi’s Dandi March and illustrations for the Constitution. Similarly, Ramkinkar’s audacious sculptures, such as the Santal Family (1938), spotlighted marginalised communities, thrusting them onto the national stage.

In the 1940s, a parallel awakening unfolded as young poets like Sukanta Bhattacharya confronted the harsh realities of hunger and human suffering. Simultaneously, young artists congregated under the Calcutta Group banner, aligning their creative expressions with these stark truths. Outside this group, artists like Chittaprosad and later Somnath Hore further intensified this narrative. The shadows cast by these traumatic experiences also left an indelible mark on post-partition artists in Bengal.

Extending the thematic exploration of artistic expressions illuminating the multifaceted journey towards freedom and awakening, the second phase of this exhibition embarks on a visual voyage through the lens of contemporary Bengali artists. Just as the struggle for Independence encompassed a spectrum of experiences, emotions, and challenges, this exhibition showcases a kaleidoscope of artistic expressions investigating individual freedom and collective awakening as a journey in progress.

The only traditional sculpture in the exhibition, cast in bronze, is Debanjan Roy's Gandhi—an icon of the Indian freedom struggle and a theme Roy has been artistically exploring for decades. While Ramkinkar Baij's famous Gandhi statue is about the heroic efforts of Gandhi at Noakhali, showing him walking across the killing fields of communalism, Roy's rendition of the icon talks of the long shadow Gandhi now casts, hinting at the imminent dark shadows that bright lights cast.

Of the two women artists in the show, in Mithu Sen’s artworks the idea of freedom or the lack of it revolves around a bleak picture of the present. She illustrates it with a dialogue between the unborn, the mother, and the motherland in her unique artistic lexicon. Her art bridges the microcosm of mother-child relationships with the macrocosm of national identity, exploring the complexities within these intimate and expansive connections. On the other hand, when the centre can no longer hold, Arunima Choudhury’s intricate portrayal of life on the fringes offers an alternative, highlighting the joy and harmony that persists in abundance at the unsung periphery. In this context, Smarak Roy playfully reminds us of India’s argumentative tradition of spirited intellectual debates and free speech— a foundational element of the Constitution and a crucial support for the entire democratic structure. His kinetic installation draws our attention to the need to articulate our thoughts and concerns. Meanwhile, in his inimitable abstract idiom, Suman Dey encourages us to embrace the unyielding struggle for liberty and self-discovery, alluding to an impending new beginning.

Debasish Mukherjee, keeping to his practice, reminds us of the deep trauma of Partition and the subsequent violence and hunger in the march to Independence. The physical hunger represented by the enormous teardrop-shaped collection of deftly made sacks with ordinary cotton cloth, which finds other usages in an arduous journey, doubles up as a metaphor for stability, a hunger for home beyond the barbed wires. Though mapped for a period, the physical displacement and emotional dissonance he elucidates extend beyond it; ripples of fear and migration are routinely felt in the ebbs and flows of national life. Like Debasish Mukherjee, Chandra Bhattacharya and Chhatrapati Dutta have also moored their artworks to a particular period. In them, the Alipore Jail assumes centre stage. Through a still-life, essentially with the help of two objects— a blanket and a mug— Chandra Bhattacharya evocatively encapsulates the imprisoned existence of the freedom fighters, quite like the fate of the migrants. The worn-out blanket and the dented metal mug testify to the cruel circumstances that deprived prisoners of their basic human dignity. Similarly, Chhatrapati Dutta pays a poignant tribute to notable and lesser-known martyrs whose names are etched in the gory history of the gallows for their unwavering commitment to the nationalist cause. Captured in evocative wash portraits, Dutta creates an alternative to existing monochromes, transforming them into vivid chronicles of courage and sacrifice.

Straddling the fundamental tenets of our democracy, as this exhibition cuts through the realms of art and history, the second phase of the exhibition invites viewers to engage visually and intellectually with the past and present discourses, paving a path for a brighter future.